We’ve all heard this tip at some point, but let’s think about this in relation to writing. I find this to be particularly important when including emotion in a story. As yourself what your character feels as she or he experiences something. What are the emotions the narrative brings out in your character? And don’t just hand those emotions to your audience; wrap them up in a description, and let readers find them on their own. Barbara Kingsolver is one of my favorite writers when it comes to description. In her novel “The Poisonwood Bible,” she describes grief like this:

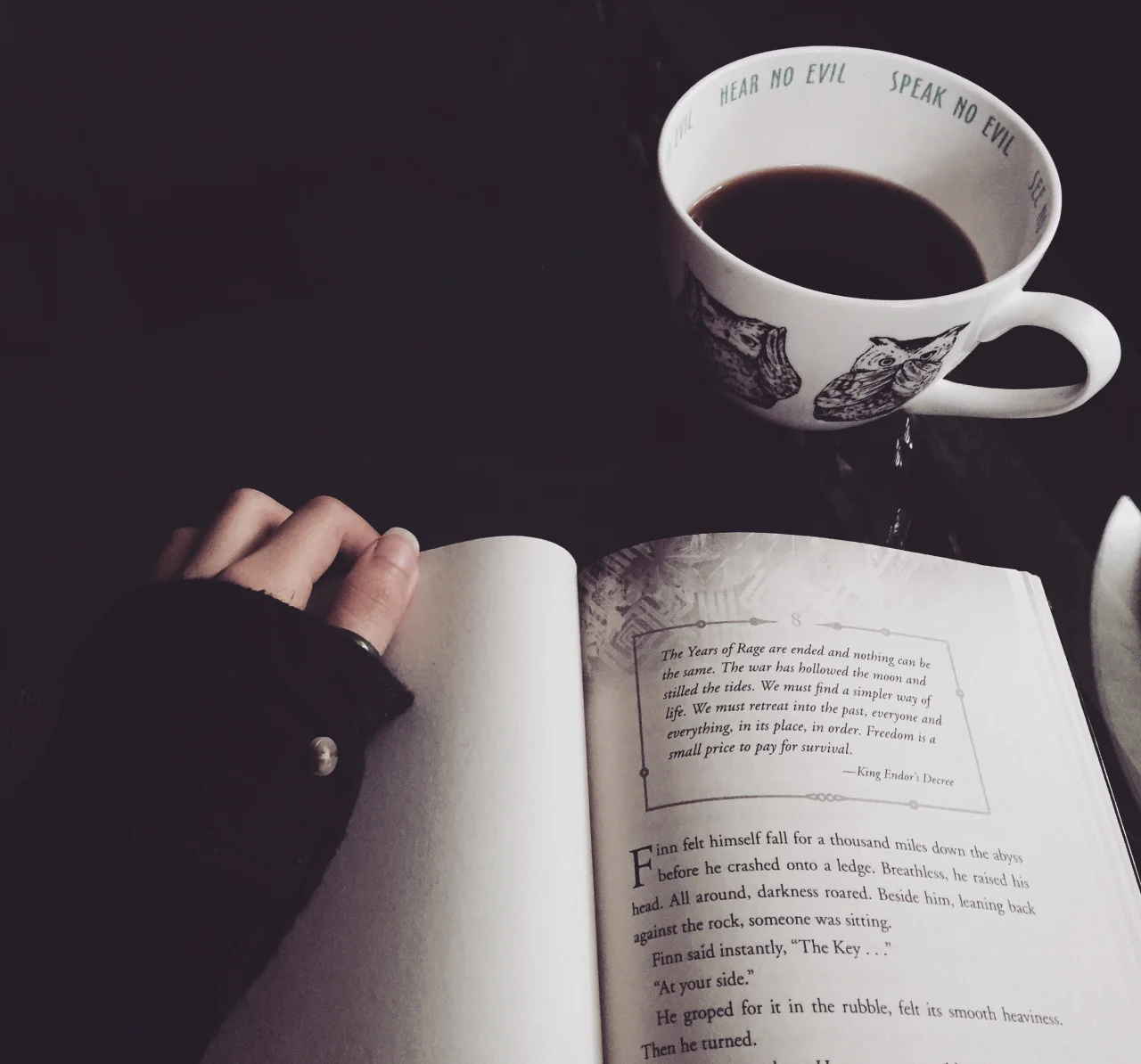

“As long as I kept moving, my grief streamed out behind me like a swimmer’s long hair in water. I knew the weight was there but it didn’t touch me. Only when I stopped did the slick, dark stuff of it come floating around my face, catching my arms and throat till I began to drown. So I just didn’t stop.”

This is a beautiful and haunting description of an emotion that almost everyone can relate to. However, Kingsolver doesn’t just say, “I was grieving.” She shows the audience instead of telling them, and what an effect that has!

2. Keep it simple

This is where most description goes wrong. We get all wrapped up in having these long, winding sentences that we create paragraphs impossible to get through. So, I urge you to keep it simple. You have to find the happy medium between the polar bores, as I call them: the bore with no description and the bore with too many words. Please, don’t bore your readers. One way to do this is to simply focus on one emotion for a descriptive sentence or paragraph.