Set a total word count. And while you’re at it, decide how many words you plan on writing each day. Come up with a schedule, and stick to it!

Write, edit, rewrite. As Hemmingway said, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” I wouldn’t go as far as saying there’s nothing to writing, but this should be the fun part! This is the part you love, after all.

Find some friends. Get feedback as early as possible, just so you know your work is making sense. You don’t want to have to go back and do a massive rewrite, do you? Feedback can be scary, but sometimes nothing propels you further in your craft like critique and validation.

3. Finishing

It’s time for final edits. This is the nitpicky perfecting and polishing that will really make your book shine. It seems tedious, but is crucial to the process.

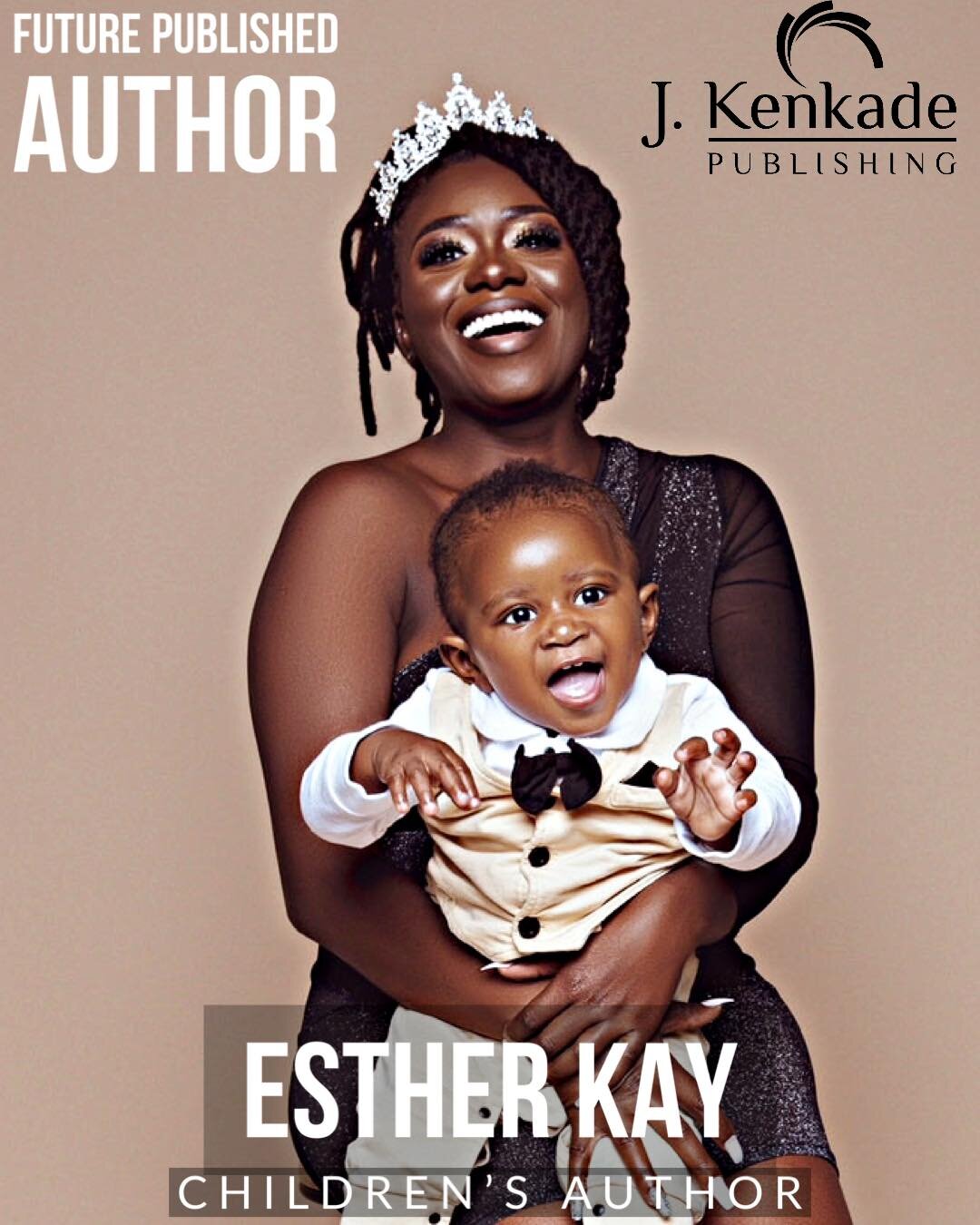

Commit to publishing. Please, please, please don’t go to all this trouble to let your manuscript sit in a drawer. I know it’s daunting to release your story to the world, but if you don’t, what’s the point?